Posthuman philosophy is a materialist vital ontology and an affirmative ethics of becoming. Materialism is an elemental philosophy, embodied, embedded, relational, and affective.

Bells render the material groundings of the posthuman predicament and their metamorphic, transformative powers: The fire-forged materiality of bells, and their airborne resonance, which engenders cosmic transmission. Bells carry us from the geological soil, to the atmospheric and planetary reverberations of sound.

All areas classified as fit for human habitation—cities, farmlands, factory sites, and their logistical infrastructural systems—are trans-species locations. Even the most technological sites—and especially the most technological sites—depend on the temperature, the soil type, and the amount of light and water, on bacteria and a myriad of non-human factors, in order to function.

All of these elemental apparatuses contain high degrees of information: Bells are one of humanity’s earliest communication technologies—bodies of metal encoded with signals, pulled by ropes, engineered to resonate—they are regulated by a distinctive code, which is as ancient as our culture. Bells convey profound systems of meanings. Their metamorphic potency is staggering: Bells turn to sound, silence, and warnings; in times of war they are melted to make cannons. They force a reconsideration of what it means to be human.

In terms of reflexivity, they push critical thinking towards a double displacement: beyond humanism and beyond anthropocentrism.

The material and the ethereal, the technological and the ecological, entangle with the social in our efforts to make sense of life beyond the human. Lynn Margulis teaches us that we carry elements of the ocean from whence we emerged, and of the soil, in the calcium of our bones, and the slightly salty plasma in our veins. We are built symbiotically from re-existing life-forms.

Analogously, with bells, metals and earth become the sonic and air, the material and the ethereal, the technological and the ecological, entangle with the social in our efforts to persist in our existence—to survive and make sense of our lives. Life, however, stretches beyond the human—but our scientific minds are not trained to think in such holistic ways.

Holism is messy, scientific thought is clear-cut, incisive, instrumental. It uses disciplinary boundaries as partitions and the practice of science as a tool of selection and governance. As Foucault taught us, institutions decide what is scientifically valid and what is to be discarded, but there is always much more discursive production circulating than scientific institutions can control and govern, especially in advanced, research-driven capitalism. It is significant, for instance, that someone like Lynn Margulis could not get her research funded by National Research Councils, because it explicitly criticised the dominant scientific ethos of her days—the theory of “the selfish gene”.

Thinking in posthuman times complicates the picture even further. Having to hold in some sort of balance in our minds the immanence of life-systems, the politics of our locations, relational ethics, and political resistance to authoritarian regimes is asking a lot. A real lot.

Relational and affective environmental grounding is both intimate and planetary, heterogeneous and yet finite: the more-than-human is us, so we are a multitude of nomadic assemblages. Till now nomadic subjects may have seemed a radical chic option—now it is a matter of great collective urgency. Together, we need to create a heterogeneous cartography of where we might be going, or rather of where we will have been in the trajectories that brought us here. Genealogical, bibliographic, affective, random—the pathways that led us here are as many as our life itineraries, and just as incommensurable. We are called upon to draw a speculative cartography that is multi-scalar and poly-directional, grounded in the present but looking elsewhere. We all know, when we can bear to think about it, that if we are to think clearly about our predicament, beyond the rage and the despair, we know that what we must do is to write the pre-history of a future.

Projected in all directions at once, on a thousand plateaus of becoming, we are all relics of a future that is still virtual, and hence totally real, except that it is not fully actualised yet, it is still in process. Between the ‘no-longer’ and the ‘not-yet’.

Our task as thinkers and artists is to reach an adequate understanding of these complex locations and multiple intersections, by drawing adequate cartographies. We have to broaden the horizon of what is thinkable and what can be endured, so as to create collective horizons of hope. Welcome to the affirmative posthuman condition!

Technology: the contradictions of the Fourth Industrial Revolution. The first peal of bells is rung against the dominant philosophy of technology of our culture: the transhumanist project that sustains the Sixth Industrial Revolution, with technological interventions ever more pervasive and invasive. Cognitive capitalism’s predatory incursions into living matter have taken over our embrained bodies and embodied brains. Information technologies, genetics, and regenerative medicine, neural sciences and the Life sciences in general do not just improve living matter—they replace it, both in human and non-human entities. The control over the self-organizing potency of living systems is financially rewarding in a neoliberal cognitive economy. Through such practices of capitalization, new marketable bits of life come into circulation that blur the categorical divides between humans and non-humans. This ruthless financialization creates a paradoxical new equality of exploitation between them.

Transhumanism believes that technologies enhance, improve and ultimately replace the human, multiplying his capacities (the gender is not casual). Transhumanism is a technology-driven human enhancement method, currently applied to fields such as medicine, health care, agriculture, and a range of industrial applications, including automated weapons and armaments. Neither the environmental, nor the social consequences of this phenomenon, let alone their effect on the construction of subjectivity, are considered by the transhumanists, whose most visible political spokesperson is Elon Musk and chief scientists Nick Bostrom and James Lovelock. Their avoidance comes with overdoses of displaced optimism.

The critical point being that human enhancements and expansions do not happen in a vacuum, but in a world where power relations are structured by sexualized, racialized, and naturalized hierarchies, and by an extraordinary concentration of capital and profits. There is a strident contradiction in transhumanism between the promises of human perfectibility of their technologies and the return to traditional and even reactionary socio-economic power formations. The term “technofeudalism” (Varoufakis, 2023) has been evoked to describe the existential threats posed to democracy by the transhumanist project of the tech-billionaires.

At the philosophical level, the transhumanists produce another salient contradiction: they are post-anthropocentric and neo-humanist at the same time. The post-anthropocentrism builds on their analyses of the advantages of computational systems over the human brain, but when it comes to norms and values, they call themselves neo-humanists proclaiming their desire to complete the rationalist project of the European Enlightenment. I am highly critical of this position.

From my critical posthuman angle, transhumanism is a corporate kind of recreation of humanity—an opportunistic pan-humanism—that makes the wrong promises. It delivers far more than it promises, because it obliterates the role of exclusions and differences in the constitution of the European idea of human/‘Man’. Moreover, it has allowed a dangerous concentration of wealth and power in the hands of the Big Tech companies. This tension between promises of human liberation and the reality of monopolies and oligarchy opens one of the great fissures of social and political crises of our times. If the bell of intolerance tolls for one category, it tolls for all.

In an affirmative posthuman perspective, the issue can be set up in a more honest and coherent manner: if the technological artifact is now our second nature, reaching new levels of complexity, we need to work within this nature-culture continuum and take the next step.

This next step need not be linear or uni-lateral: it can be multi-directional and rhizomatic. For instance, we could take the genealogical road and ask ourselves: what are the historical and genealogical ancestors of the contemporary information technologies? How many previous communication codes did Western culture invent? If it is indeed true that a bell is not a bell till someone rings it, then what is being communicated by ringing it? What does it mean that the medieval motto of the bell ringers is “VIVOS VOCO. MORTUOS PLANGO. FULGURA FRANGO”—“I mourn the dead, I call the living, I break the lightning.” How does that work? Can you decode the ringing of the bells in a city like Rome, which is talking to you incessantly through these metal chambers of resonance pulled by ropes and human muscles? What does it mean that there is a Liberty Bell in Philadelphia and a Freedom Bell in Berlin? There is a genealogical route.

And then we could take the ethical route of acknowledging our interdependence as humans and propose a renewed collaborative ethics in relation to both the technologies and their environments. Please note that this is not a flat ontology, but a material differential one: it also allows us to rethink the specific features, values, and pleasures of the anthropomorphic beings that we humans are, without giving in to our ancestral anthropocentrism.

If we agree that humans today are heterogeneous assemblages of the organic and technological, in working together to achieve a better—more adequate—understanding of the web of social and technologically mediated relations that constitute our subjectivities and our relation to the world, we are also weaving a web of peace and collaboration with and in this world. It is the only world we have, and this uniqueness may convince us to all come to a consensus about our obligation to take better care of it.

A grounded critical posthuman perspective is a gesture of care and a critique of the transhumanist delusion of flight from the body, the flesh and the earth, which is our planet. An affirmative approach does not reject the technologies, but embeds them in more complex ecologies—environmental, social, and affective. It also enfolds them inwards, towards a nomadic understanding of the posthuman subjects as a heterogeneous assemblage related to multiple non-humans. Posthuman affirmative ethics are another route.

And we should definitely take the political route: ring the bells that still can ring freely. We must decide collectively and democratically how to manage and regulate the technologies which frame our posthuman lives. We need to resist a one-size-fits-all model of posthuman evolution and replace it with community-led experiments with a diversity of models of relating to the forms of enhancement and human-machine interaction that technologies today afford us. Different communities may choose their own ways of becoming posthuman. For instance, many Indigenous nations are taking the lead in the diversification of options, through data sovereignty actions, Rights of Nature laws, and decolonial perspectives.

The experiments with what kind of posthumans we become, may also involve, quite flatly, the refusal to take the posthuman turn altogether. Stewardship of and care for the Earth can be another response to the advanced technologies, which consume so much energy and other geological resources. Some Earthlings may choose democratically not to be enhanced and to stay close to their home base. In any case, the issue of which values and normative frameworks apply to the posthuman predicament is a task for the whole citizenry not only for official institutions and corporations.

In discussing possible regulatory frameworks for a posthuman democracy, I am especially concerned to defend the rights of the sexualized, racialized, and naturalized ‘others’ of Man: women, LBGTQ+ people, Indigenous, Black, colonized people, and the non-humans. Advanced technologies that claim to improve ‘humanity’ and at the same time wipe out all social and symbolic power differences between these entities are inadequate. They are also potentially quite threatening to the process of reaching a community-driven redefinition of what it means to be human in a posthuman era. That is the affirmative mode.

Conclusions:

All visionary—critical and creative—movements believe in the importance of the radical imagination and support specific forms of creativity, as shown in science fiction, fantasy novels, utopian texts of a political or fantastic nature, and also through Afrofuturism and Black space-travel narratives.

The speculative genre voices the transversal alliance of sexualized, racialized, naturalized others against the dominion of Man/Anthropos. It combines dystopian and utopian elements in envisaging alternative feminist futures. This is all the more relevant today, given the economics and politics of the contemporary space race and the search for new materials in far-away regions of our Galaxy, on Mars and in outer space. This transformative aspiration, however, remains rooted in a deeply materialist thought, which stresses the embodied, embedded, and sexuate roots of all material entities, humans included. We remain earthlings.

The strength and relevance of new-materialist thought is to defy binary oppositions by thinking through embodiment, multiplicity, and differences. Posthuman thought challenges the opposition of nature versus culture and argues for a ‘natureculture’ continuum to enable a better understanding of the mutual interdependence of human and non-human others. It also proposes new relational practices and ethical values to strengthen cross-cultures and cross-species collaboration. And renews relation to Indigenous epistemologies. Easier said than done.

But the ways of the radical political imagination are infinite. We are all parts of the same ecosystem, which is the cosmos!

Nothing is played out—so let us display our powers of thinking and imagining possible futures.

Because we are in this together, though we are not all one and the same.

To paraphrase the great poet John Donne:

No man’s an island entire of itself(…)

Any man’s death diminishes me,

because I am involved in mankind

And therefore

Ask not for whom the bell tolls,

It tolls for thee.

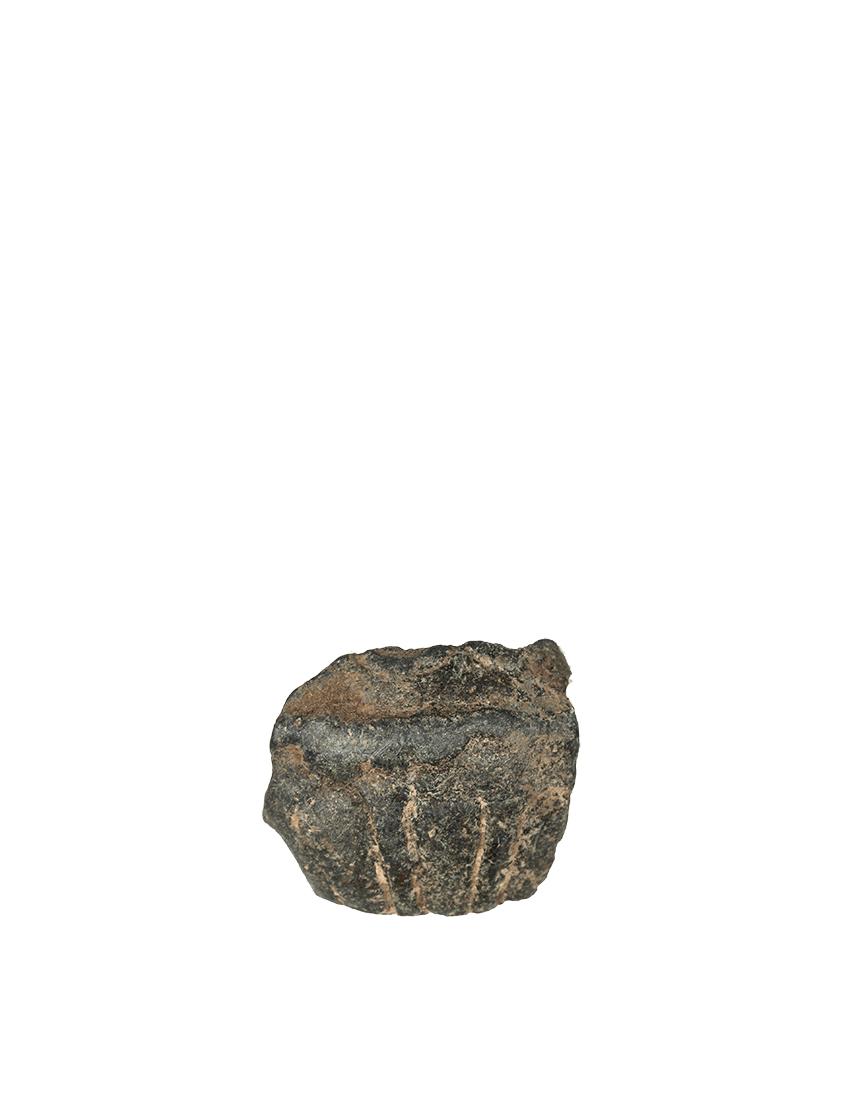

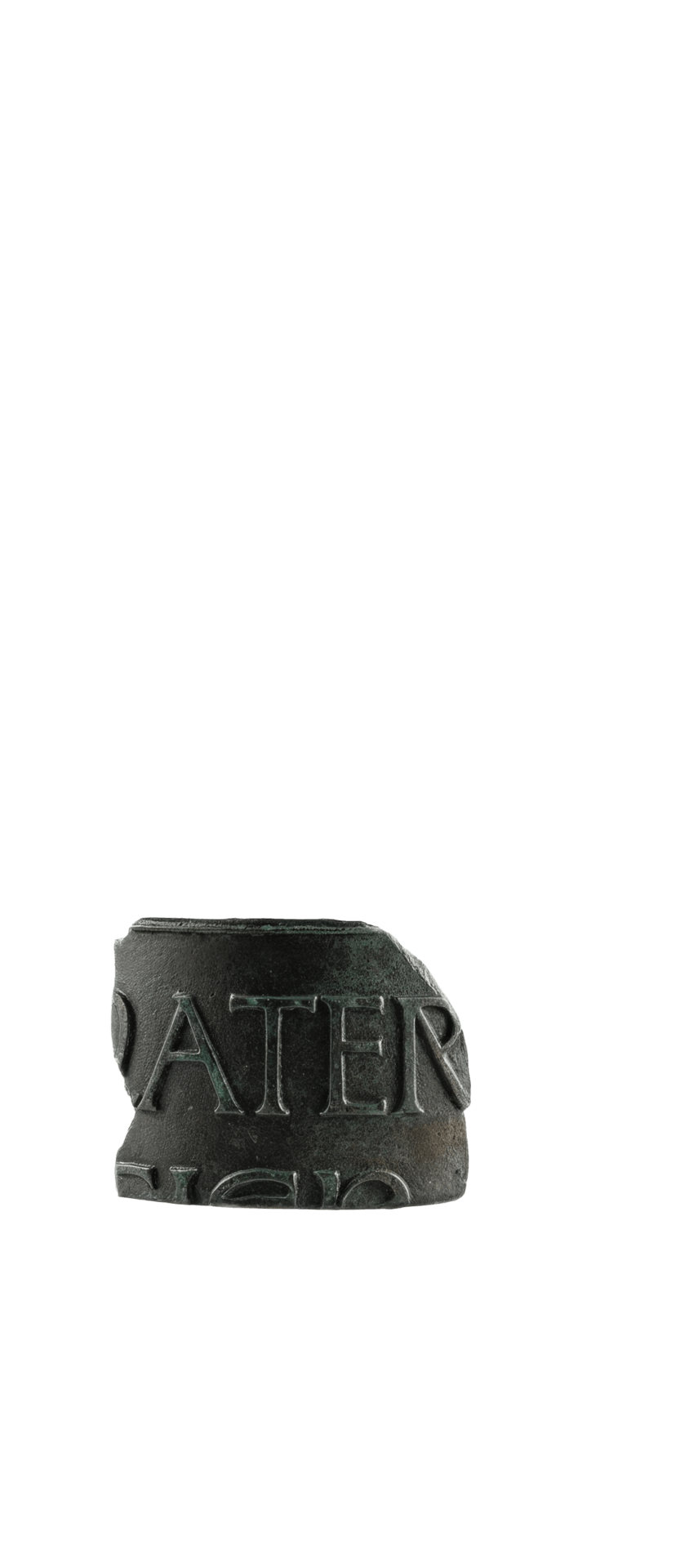

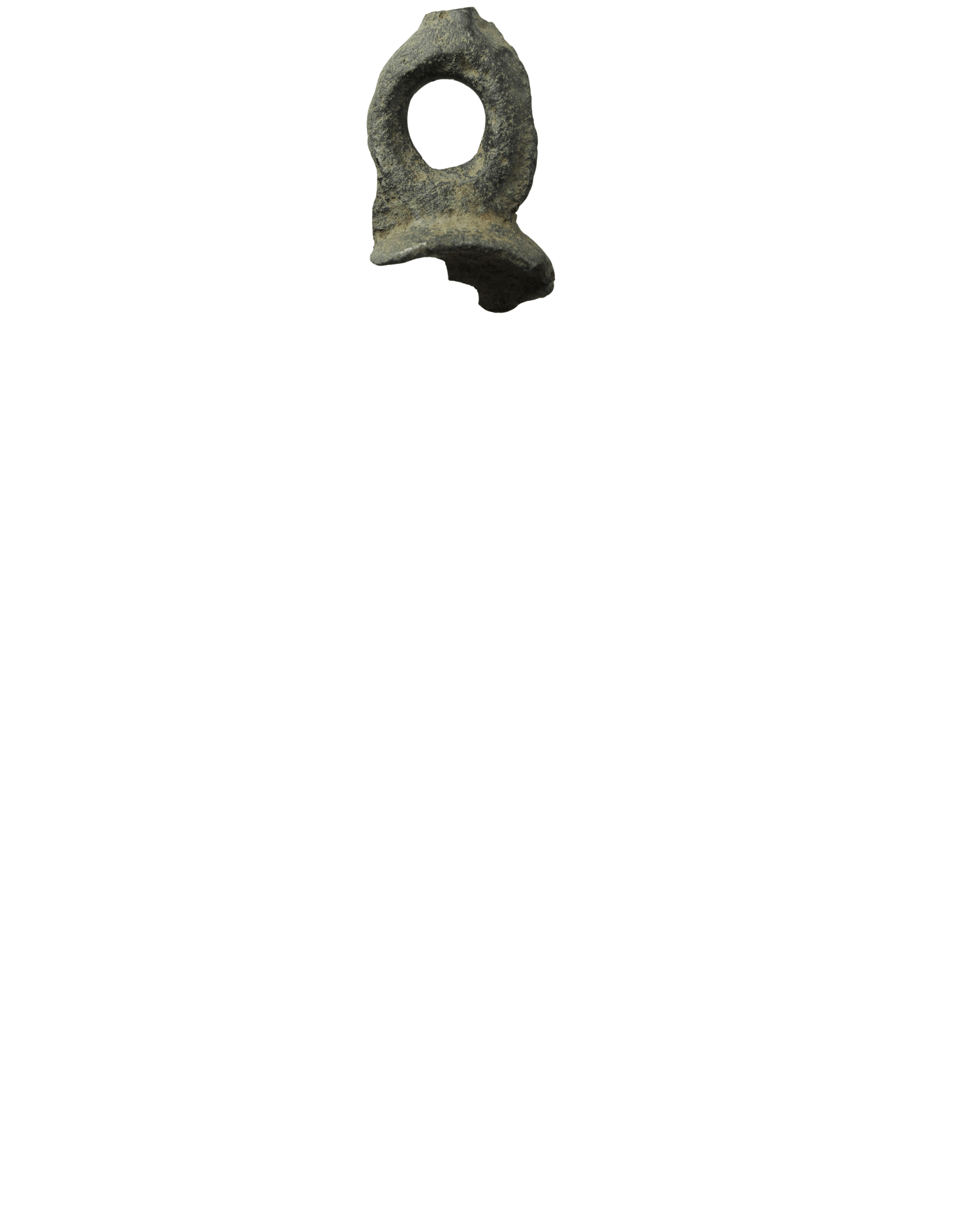

Click a bell fragment to uncover what it has carried through time. If a message is inscribed, click again to reveal additional insights.

Rosi Braidotti

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet consectetur adipisicing elit. Aperiam totam consequatur earum nemo quod quo eligendi architecto enim voluptate cupiditate corporis, ducimus nisi. Nostrum quaerat corrupti enim adipisci quas libero! Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet consectetur adipisicing elit. Nemo cumque fugit porro, eum minus eveniet recusandae numquam quas hic voluptatum dolores maxime quam, quia aliquid dolorem quidem ex minima excepturi.

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipisicing elit. Necessitatibus nulla, at culpa animi aut facilis reiciendis voluptate ratione cupiditate qui perspiciatis, assumenda nostrum saepe deserunt quia veniam accusantium error suscipit!

Material Signal

Bells are one of humanity's earliest communication technologies—bodies of metal encoded with signals, pulled by ropes, engineered to resonate—they are regulated by a distinctive code, which is as ancient as our culture. Bells convey profound systems of meanings. Their metamorphic potency is staggering: Bells turn to sound, silence, and warnings; in times of war they are melted to make cannons.

The fire-forged materiality of bells and their airborne resonance engender cosmic transmission. They carry us from the geological soil to the atmospheric and planetary reverberations of sound. Each toll transforms metal and air into message and memory, linking the human hand to the forces of the cosmos.

Affective Resonance

The bell's metamorphosis never ceases. It turns matter into vibration, vibration into atmosphere. Every ringing disturbs the air, creating a moment of suspension—an interruption in the flow of time. In this disturbance, resonance becomes affect: a vibration that passes through bodies, technologies, and worlds.

Some bells toll without being heard; others wait in silence until the time is right. Each echo is a repetition with difference—shaped by wind, distance, humidity, and history. Through such transformations, the bell becomes a living interface between the material and the emotional, a conduit of shared intensity. In its sounding, we sense the connective tissue of existence—the way feeling itself reverberates across scales, from the cellular to the planetary.

Ethical Attunement

What are the historical and genealogical ancestors of contemporary information technologies? How many previous communication codes did Western culture invent? If it is indeed true that a bell is not a bell till someone rings it, then what is being communicated by ringing it? What does it mean that the medieval motto of the bell ringers is "VIVOS VOCO. MORTUOS PLANGO. FULGURA FRANGO"—“I mourn the dead, I call the living, I break the lightning.”

This ancient motto evokes the titanic contest between bell and thunder. It recalls a time when ringers believed their sound could shatter storms, transforming the city into a resonant chamber between earth and cosmos.

To listen in posthuman times is to attune to this continuum—to the shared vibration of matter and meaning. Bells remind us that every technology of sound is also an ethics of care. Each toll calls us into relation, turning resonance into responsibility, and echo into empathy. To listen is to become planetary: to hear the future ringing through the present.